**The Sandworm’s Enigma: A Novel Direction for Materials Science**

The seemingly ordinary sandworm, Nereis virens, has unintentionally contributed to a revolutionary advancement in materials science. This marine annelid builds its jaw using a durable biological composite infused with zinc ions. Upon extracting the zinc, researchers discovered that the structure not only diminished in strength but also became vulnerable to water. This finding piqued the interest of Javier G. Fernández, a materials engineer at the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia in Barcelona.

Fernández speculated that this principle could be reversible: it might be feasible to use metal ions to influence how biological materials engage with water instead of resisting or isolating from it. The result of this concept is an innovative material presented in Nature Communications. Fernández and his team produced a bioplastic from discarded shrimp shells that actually gains strength when exposed to water, an achievement no prior synthetic bioplastic had reached.

The material is made from chitosan, a polymer sourced from chitin—the structural component in crustacean shells—combined with nickel ions. In aqueous environments, thin chitosan layers enriched with nickel grew 50% stronger, rivaling tough engineering plastics like polycarbonate, while remaining competitive with common plastics like polypropylene in dry settings. This sophisticated innovation relies on cooperative interactions with its surroundings rather than isolation from it.

The persistent challenges related to traditional plastics are complex. Their resistance to water makes them essential yet environmentally harmful, as these plastics build up as waste, especially in aquatic habitats. Bioplastics have not yet offered a practical solution. They generally weaken when exposed to moisture, prompting engineers to resort to chemical alterations or protective coatings, which contradict their environmentally friendly intention.

Instead, Fernández’s team adopted an unconventional viewpoint. “For more than a hundred years, we have believed that, to succeed in nature, materials must become inert,” Fernández noted. “This research demonstrates the contrary: materials can flourish by engaging with their environment rather than withdrawing from it.”

The underlying mechanism of this finding involves integrating nickel ions—micronutrients noted for their solubility and interaction with chitosan—into the chitosan structure during production. When immersed in water, 87% of the nickel is released, but approximately one ion for every eight sugar rings of the polymer chain remains, creating a dynamic, reversible array of weak bonds. This network continuously breaks and reestablishes, absorbing and redistributing stress, rendering the material resilient despite being “soft” at the molecular level.

This groundbreaking method questions established materials science beliefs. Conventional engineering materials derive their strength from rigid bonds that exclude water. In contrast, the chitosan-nickel composite incorporates water as a vital element, preserving a self-organizing network. While this behavior resembles certain natural biological formations, it had not been artificially replicated until now. Experiments substituting nickel with zinc or copper ions indicated that the effect is likely specific to nickel’s chemistry.

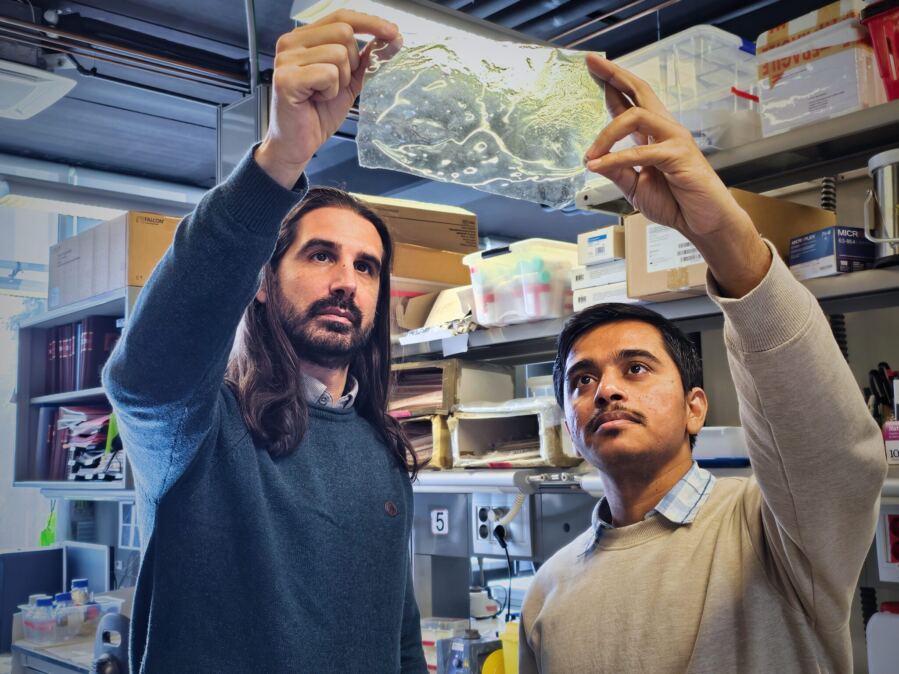

Importantly, the process is zero-waste. The nickel leached from the initial batch enriches the water, which in turn becomes feedstock for subsequent batches, thereby maximizing nickel utilization. As Akshayakumar Kompa, the study’s lead author, remarked, “Each year, the world produces an estimated one hundred billion tonnes of chitin,” making chitosan abundantly accessible from shrimp and crab waste or through organic waste bioconversion.

In lab evaluations, the team successfully scaled production, generating films up to three square meters without processing issues and crafting water-retaining cups without leaks. Future applications may encompass biodegradable agricultural films, fishing equipment, and packaging. Medical applications may also be feasible, considering that both nickel and chitosan are FDA-approved for specific uses, although their combination has yet to be assessed.

The team is hopeful that other ions might replicate or even amplify this effect, opening doors for further exploration into alternative materials. This study signifies the onset of a new era in materials science. As Fernández rightly states, “Now that we understand this effect exists, we and others can seek new materials and innovative methods to achieve it.”

The sandworm, without a doubt, remains oblivious to its influence.

Study link: [https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-026-69037-4](https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-026-69037-4)