Somewhere within a doughnut-shaped apparatus in California, a flow of superheated plasma is racing at approximately 88 kilometers per second. It is also, in a way, disintegrating. Particles at the periphery of the magnetic field that confines the plasma are perpetually breaking free, cascading downward toward metal plates meant to capture them, cool them down, and return them to the action. The incoming atoms assist in sustaining the fusion reaction. However, there’s a catch: they don’t land where one would anticipate.

For years, physicists conducting tokamak experiments have detected a persistent imbalance. A significantly larger number of escaping plasma particles collide with the inner exhaust target compared to the outer one. This pattern has consistently emerged across various machines and conditions, leaving researchers at a loss to explain it.

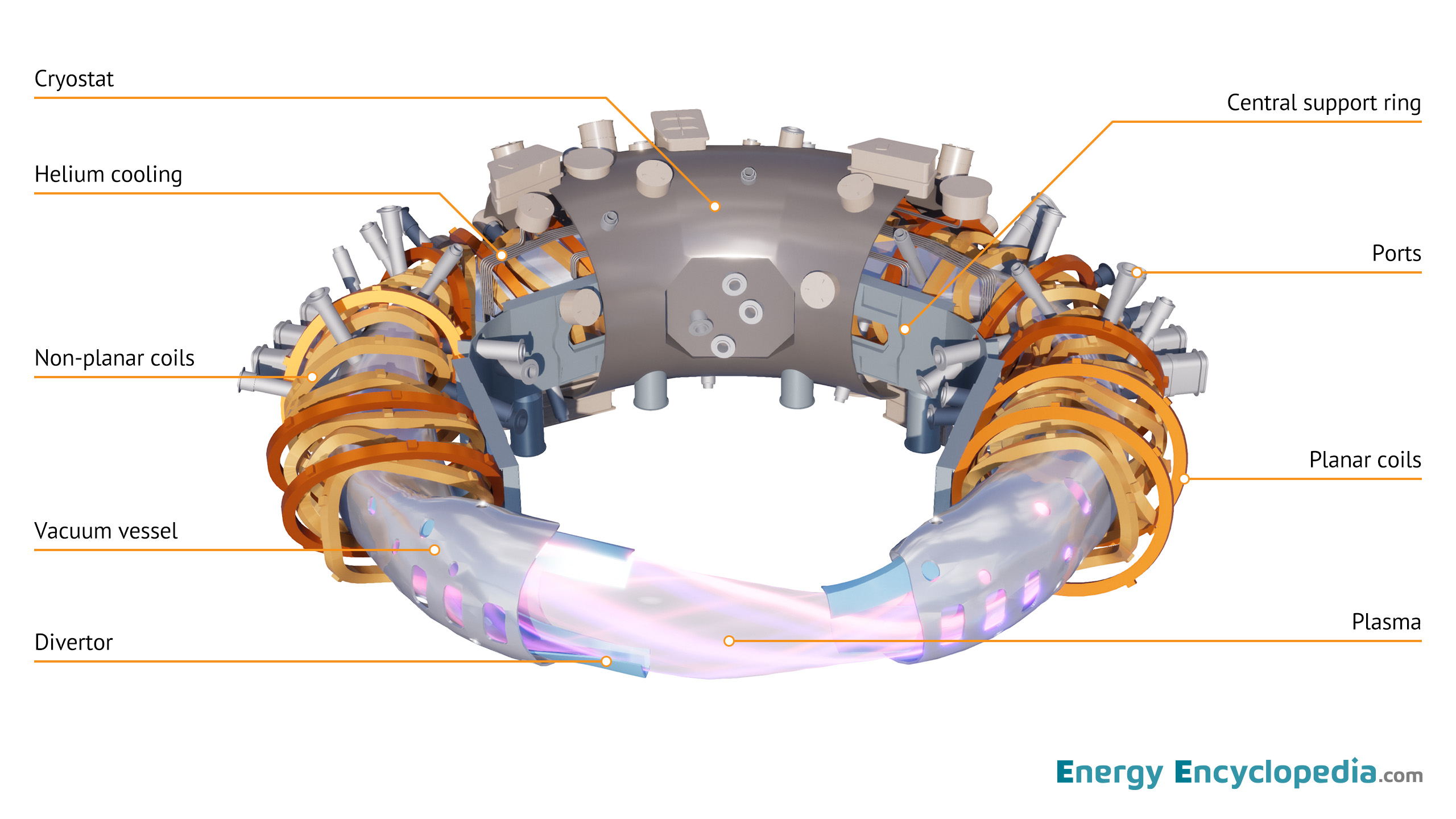

This discrepancy is more significant than it might seem. If fusion reactors are ever to operate for decades (which is, ultimately, the goal), engineers must accurately predict where those exhaust particles will impact. Miscalculations can lead to uneven erosion of metal plates, the formation of hotspots in inappropriate locations, and components failing prematurely. The exhaust system of a tokamak, referred to as the divertor, requires precise engineering informed by sound physics. Until recently, the physics was not aligning.

The primary theory revolved around what are termed cross-field drifts, the lateral movement of charged particles across magnetic field lines in the divertor area. Reasonable enough. However, when researchers created computer simulations that incorporated only this effect, the results did not align with experimental findings. The imbalance in the models was never sufficiently pronounced.

Now, a team led by Eric Emdee, an associate research physicist at Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, believes they have identified the missing piece. Utilizing the modelling code SOLPS-ITER, Emdee and colleagues simulated plasma behavior in the DIII-D tokamak under four distinct scenarios, toggling cross-field drifts and plasma rotation on and off in various combinations. The findings, published in Physical Review Letters, illustrate how two mediocre explanations can merge into one highly effective explanation.

“There are two components to flow in a plasma,” states Emdee. “There’s cross-field flow, where particles drift sideways across the magnetic field lines, and parallel flow, where they move along those lines.” The prevailing belief had favored cross-field flow as the cause of the asymmetry. “Many suggested cross-field flow was responsible for the asymmetry,” he notes. “What this paper demonstrates is that parallel flow, prompted by the rotating core, is equally important.”

Individually, adding rotation to the simulations adjusted things somewhat. The same applies to cross-field drifts alone. Neither could replicate the experimental data. However, when Emdee’s team integrated both effects, incorporating the measured core rotation speed of 88.4 kilometers per second, the simulations finally aligned with the observations physicists had made for years in the actual machine. The combined effect proved significantly greater than either component acting alone, revealing a synergy between the two flow mechanisms that alters how momentum is transported across the plasma edge and, ultimately, how many particles reach each divertor target.

It’s an impressive finding, and a reassuring one. Fusion engineers cannot merely create a prototype divertor, operate it for 20 years, and see the outcome. They require simulations they can rely upon.

What Emdee and his team have demonstrated is that the existing boundary plasma models can achieve this, successfully replicating the persistent asymmetries that have perplexed physicists, provided one accounts for both rotation and drifts working in tandem. That “provided” carries a significant weight.

The research included contributors from PPPL, MIT, and North Carolina State University, conducted using the DIII-D National Fusion Facility. While alone it won’t resolve the engineering challenges of constructing a commercial fusion reactor, it does chip away at one of those elusive unknowns that, if left unresolved, could quietly jeopardize the entire endeavor.

For the engineers assigned with designing exhaust systems that may need to endure decades of assault by runaway plasma, pinpointing where the particles actually land isn’t a trivial detail. It could very well be the critical detail.

Study link: [https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/zjpv-vxwd](https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/zjpv-vxwd)