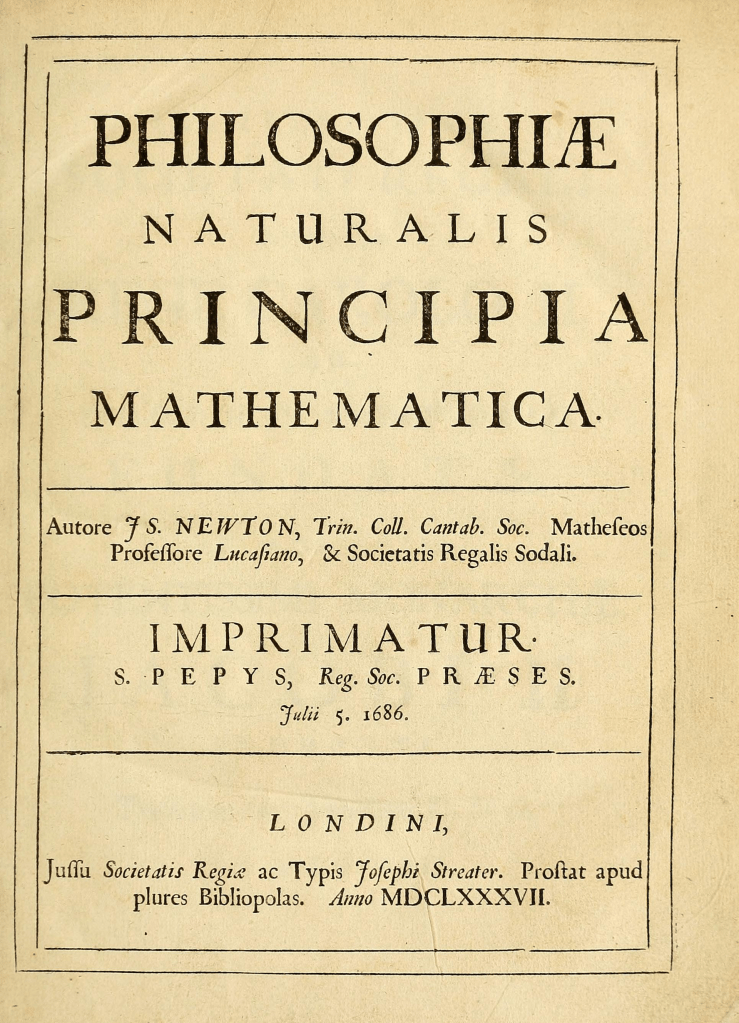

In the exaggeration of the popular narrative surrounding the history of science, Newton’s *Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica* (*The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy*) is frequently regarded as one of the most pivotal works in the scientific domain. Typically, many esteem it highly due to Newton’s identification of the law of gravity. Nevertheless, it is more precise to assert that Newton validated the law of gravity, which differs from simply discovering it. The essential reason for the importance of Newton’s *Principia* lies in its illustration that there are coherent laws of mechanics applicable to both earthly and heavenly realms, shattering a longstanding dichotomy in natural philosophy put forth by Aristotle two millennia prior.

Aristotle categorized the universe into two distinct zones: the sublunar (everything beneath the Moon’s orbit) and the supralunar (everything above the Moon’s orbit). He claimed that different principles governed motion in these domains, establishing separate celestial and terrestrial mechanics. Although the Stoics opposed this dichotomy, Aristotle’s framework dominated for centuries.

Aristotle posited that the only natural motion in the sublunar realm was a direct fall to Earth, for which he constructed a now-disproved mechanical theory. In the sixth century, John Philiponus challenged Aristotle’s theories, proposing concepts that would develop into the impetus theory regarding projectile motion. Subsequently, Islamic scholars built upon Philiponus’ ideas.

In the fourteenth century, the Oxford Calculators and Paris Physicists anticipated much of Galileo’s exploration of the laws of falling. During the sixteenth century, Tartaglia made additional strides in understanding projectile motion. Moreover, Giambattista Benedetti established much of the theory surrounding falling bodies ahead of Galileo.

As the seventeenth century approached, Guidobaldo dal Monte and Galileo illustrated that the trajectory of a projectile is parabolic, while Isaac Beeckman introduced the accurate law of inertia. Galileo experimentally validated the accurate claims of the Oxford Calculators, challenging Aristotle’s theories.

Despite these developments, Aristotle’s dichotomy persisted largely unchanged until the sixteenth century. He maintained that celestial motion was flawless, uniform, and circular, categorizing comets as atmospheric events. It was not until the fifteenth century that astronomers like Toscanelli began to view comets as celestial objects, which contradicted the Aristotelian perspective. The debate regarding the nature of comets intensified in the 1530s alongside a revival of interest in Stoicism.

The supernova of 1572 and the great comet of 1577, both located above the Moon’s orbit, significantly undermined Aristotle’s cosmological framework. As these occurrences transpired, astronomers devised new models opposed to Aristotelian doctrine. The heliocentric theory posited by Copernicus and Tycho Brahe’s geo-heliocentric model ignited tensions between astronomers and philosophers.

In 1609, Johannes Kepler introduced elliptical orbits along with three laws of planetary motion, leveraging Tycho Brahe’s observations. He proposed that a force similar to magnetism drives the planets’ orbits—a conceptual predecessor to the idea of universal gravitation. By 1666, Giovanni Alfonso Borelli expanded on the notion of forces influencing celestial movements.

In the realm of terrestrial mechanics, Torricelli’s invention of the barometer contested Aristotle’s assertion regarding the impossibility of a vacuum, while Pascal’s research confirmed the presence of air’s weight and the existence of a vacuum. Nevertheless, Descartes adhered to a corpuscular hypothesis featuring vortexes rather than accepting gravitational forces.

The gradual decline of Aristotelian ideas over centuries prepared the way for Newton. As a scholar, he found a well-developed groundwork in terrestrial mechanics, unified by figures like Christiaan Huygens, while celestial mechanics still faced disputes. By adapting and amalgamating existing theories, Newton unified terrestrial and celestial mechanics into a singular cohesive framework.

In future discussions, we will delve into how Newton, faced with an array of mechanical theories, integrated and transformed them into a unified scientific canon.