Each inhalation you take in a contaminated urban environment brings more than just oxygen. Suspended in the atmosphere are minuscule particles that can remain airborne for extended periods, smaller than bacteria and capable of penetrating deep into lung tissue, entering the bloodstream, and potentially finding their way into the brain. A recent investigation involving nearly 28 million senior Americans has bolstered this claim, suggesting that prolonged exposure to fine particulate pollution heightens the risk of Alzheimer’s disease, apparently affecting the brain directly, rather than through conditions such as heart disease, hypertension, and depression.

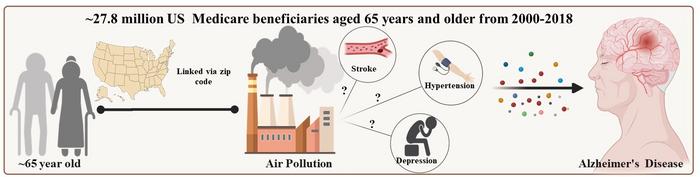

This revelation is significant as Alzheimer’s disease, which impacts around 57 million individuals worldwide and is expected to triple by 2050, currently has no cure. While factors like age and genetics cannot be modified, air quality presents a changeable risk factor. The research led by Yanling Deng at Emory University, published in PLOS Medicine, utilized Medicare claims over the past twenty years, linking the onset of Alzheimer’s with preceding pollution levels, particularly PM2.5 particles, surrounding participants’ residences. Of the 27.8 million examined, 3 million developed Alzheimer’s, with every increase of 3.8 micrograms per cubic meter in pollution translating to an 8.5% increase in risk. This pattern persisted across various demographic and health-related parameters.

The Emory research team aimed to explore the mechanisms through which pollution impacts Alzheimer’s. Traditional beliefs indicate that conditions such as hypertension, stroke, and depression, associated with poor air quality, heighten the risk of Alzheimer’s. However, the mediation analysis from the study showed that these factors accounted for only a small portion of the pollution-Alzheimer’s relationship: hypertension 1.6%, depression 2.1%, and stroke 4.2%. More than 90% of the connection appeared to bypass these intermediaries, suggesting direct impacts on the brain—PM2.5 particles may penetrate the blood-brain barrier, triggering neuroinflammation and oxidative stress. Early signs of Alzheimer’s have already been detected in children and young adults from polluted areas post-mortem.

Importantly, stroke survivors demonstrated increased vulnerability to pollution’s Alzheimer’s risk, experiencing a 10.5% rise per exposure increment compared to a general increase of 8.5%. This could be related to their weakened blood-brain barrier, which facilitates the entry of harmful particles. Consequently, those with a history of strokes are especially at risk from the negative effects of polluted air on their brain health.

The large dataset from this study provides strong findings, surpassing smaller European studies that previously indicated cardiovascular diseases played a significant role in mediating pollution’s effects. Nonetheless, these studies failed to account for the interactive effects between pollution exposure and mediating conditions, leading to distorted outcomes. After adjusting for these interactions, the findings align more closely with the Emory research.

Despite its advantages, the study has shortcomings. Pollution exposure was estimated based on zip-code rather than at an individual level, and did not consider indoor pollution sources, such as cooking. The predominantly white cohort limits the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, the five-year exposure timeframe neglects historical influences on participants’ health.

The recommendation regarding policy is straightforward: decreasing PM2.5 levels may more effectively reduce Alzheimer’s cases than focusing exclusively on cardiovascular risks. For stroke survivors, outdoor air represents a significant threat to their cognitive health, highlighting an urgent public health issue. Study link: [https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1004912](https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1004912)