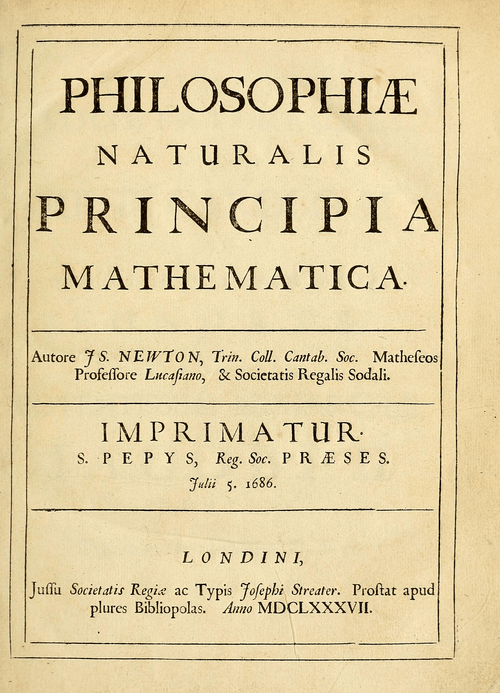

In the earlier episode of this series, I examined the two English mathematicians who had the most impact on the young Isaac Newton (1642–1726 os) during the initial phases of his intellectual growth, Isaac Barrow (1630–1677) and John Wallis (1616–1703). Today, we embark on a first, likely of several, examinations of Isaac Newton, who played a crucial role in the development of physics, even though it had not yet been termed as such, when he integrated terrestrial mechanics with astronomy under the concept of universal gravity in his masterpiece, *Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica* (*The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy*) in 1687.

The widespread exaggeration labels Newton as the greatest scientist of all time, which is, of course, nonsense. Beyond the anachronism of the term scientist, first introduced by William Whewell in 1831, it’s important to recognize that as late as the end of the seventeenth century, there was no concept of a professional scientist in the contemporary sense and certainly no predetermined career trajectory to become one. If we look at the timeframe from the gradual resurgence of science in the High Middle Ages to Newton’s era, the closest we find to professional scientists are the court astrologers, who were mostly also astronomers. Even Kepler, who transformed astronomy and optics, primarily worked as a professional astrologer.

Medieval universities did not take mathematics seriously, and chairs for mathematics were nearly nonexistent. They were largely Aristotelian, and what we now consider physical sciences were approached from a philosophical standpoint, not a mathematical one. When chairs for mathematics began to emerge during the Renaissance in the fifteenth century, first in Krakow and later in the Renaissance universities of northern Italy, they were primarily established to instruct astrology students in medicine due to the dominant astromedicine, or iatromathematics as it’s accurately named. To practice astrology, one needed to understand astronomy, and to understand astronomy, one had to grasp mathematics. Even in the early seventeenth century, Galileo, serving as a professor of mathematics in Padua, would have been expected to teach astrology to the medical students, although there is no direct evidence he did so.

Chairs for mathematics and/or astronomy gradually proliferated across Europe during the sixteenth century, but Britain lagged significantly behind continental advancements. In England, Henry Savile (1529–1622), who journeyed abroad to further his own mathematical education, established chairs for geometry and astronomy at Oxford University in 1619. Cambridge had to wait until 1663 when Henry Lucas (c. 1610–1663) left funds for a professorship in his will, with Charles II creating the Lucasian Chair in 1664. Newton was the second Lucasian Professor, succeeding Isaac Barrow. It’s worth noting that the Gresham chairs for geometry and astronomy, initiated early in the century, predated both university chairs, but these were not actual teaching positions; rather, they were public lectures aimed at a broader audience. Henry Briggs (1561–1630) held both the first Gresham chair and the first Savilian professorship for geometry.

To illustrate the absence of a scientific career path in the seventeenth century, let’s briefly review the life trajectories of four scholars featured in this series, who made significant contributions to the emerging mathematical sciences.

René Descartes (1596–1650) was the child of a minor aristocrat and politician. He was educated at the Jesuit College of La Flèche, where he received a top-notch education, likely encompassing the best mathematical training available in Europe at the time. He studied for two years at the University of Poitiers, graduating with a *Baccalaureate* and *Licence* in canon and civil law. However, instead of embarking on a legal career, he set out to become a military engineer, but to achieve this, he, a Catholic French aristocrat, ventured to Breda in the Netherlands to enlist in the Protestant Dutch States Army. By mere coincidence in Breda, he encountered Isaac Beeckman, a Dutch candle maker turned educator, who introduced him to the corpuscular mechanical theory and mathematical physics. This encounter set him on a circuitous route to becoming a mathematician, philosopher, and physicist.

Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695) was the offspring of a powerful aristocratic diplomat and received an exceptional private education before attending Leiden University to study law and mathematics, followed by a time at the Orange College in Breda. His entire life had been geared toward following in his father’s footsteps as a diplomat, but after one assignment, he realized it was not for him. He withdrew to his family home and, with the support of his father, became a private scholar engaged in studying a