When the brain experiences swelling during Alzheimer’s disease treatment, it usually prompts clinicians to slow down. They reduce the infusion rate, keep a close watch on you, and allow time for the swelling to subside. This is a side effect that most would prefer to avoid. However, a small study from Houston Methodist Research Institute now indicates that these swollen areas in the brain could actually be the locations where the treatment exerts its strongest effect, breaking down amyloid plaques characteristic of the disease.

The side effect in question is referred to as ARIA-E, which stands for amyloid-related imaging abnormality with edema. It appears in some patients receiving newer anti-amyloid antibody medications such as lecanemab and donanemab, which aim to identify and eliminate sticky aggregates of beta-amyloid protein from the brain. When this occurs, plasma seeps from blood vessels into adjacent tissue, resulting in localized swelling that can be detected on MRI scans.

ARIA-E has been a persistent challenge in the realm of Alzheimer’s treatment. In clinical studies of these medications, it manifests in a significant portion of patients, especially those with the APOE ε4 gene variant, a major Alzheimer’s risk factor. Clinicians handle it with caution, pausing or reducing drug infusions until the swelling goes down, which generally takes around two months. Understandably, there are concerns about potential brain damage.

Joseph Masdeu at Houston Methodist and his team speculated that there might be something more intriguing happening. Their research, published in the American Journal of Neuroradiology, examined five patients who developed moderate to severe ARIA-E while receiving lecanemab or donanemab. All five had at least one copy of the APOE ε4 allele. Four were women, with an average age of approximately 74.

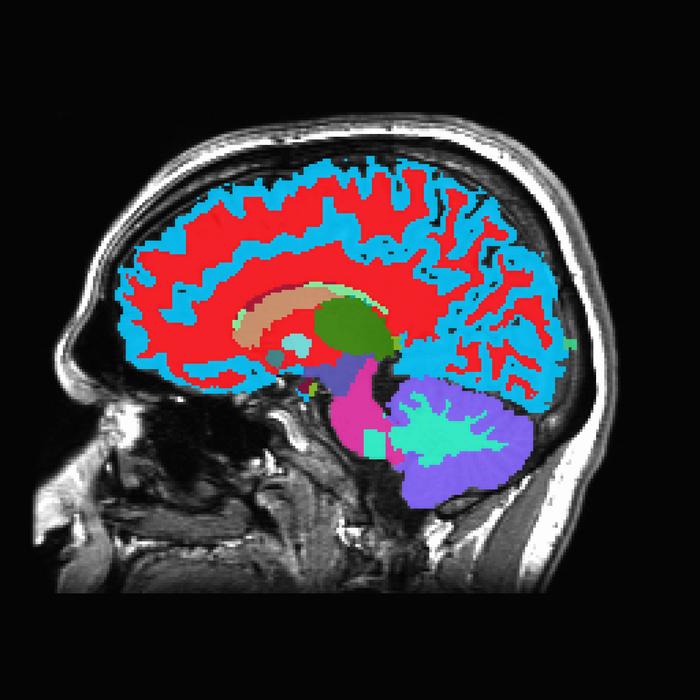

The researchers utilized PET brain scans to evaluate beta-amyloid levels before and after the swelling occurred. They divided each patient’s brain into 40 regions, then compared the reduction in amyloid in regions that had swollen with those that had not. In four out of five patients, the areas that experienced ARIA-E showed a significantly greater reduction in amyloid signal. It appeared that the swelling had a purpose.

“This study indicates that not all areas of the brain respond uniformly to anti-amyloid therapy,” Masdeu explained. “This shifts the perception of ARIA-E from merely a side effect to a potential indicator of robust local treatment activity.”

What could explain the connection between swelling and amyloid clearance? The researchers proposed several potential mechanisms. One possibility is that the antibody drugs increase the permeability of local blood vessels, allowing more of the drug to reach and clear amyloid while also causing the fluid leakage seen on scans as edema. Another explanation is that immune cells known as microglia are consuming amyloid in those areas, a process called phagocytosis, which has been observed in autopsy studies of patients treated with lecanemab. This engulfment could disguise amyloid from PET tracers without fully removing it from the brain. A third potential factor involves the brain’s waste clearance system, the glymphatic system, becoming obstructed by immune complexes accumulating around blood vessels, resulting in fluid accumulation in the white matter.

It’s likely a combination of all three, along with possibly other mechanisms.

The study comes with clear limitations, and Masdeu’s team is transparent about them. Five patients is a small sample. All were carriers of the APOE ε4 allele, so the findings may not apply to individuals with varied genetic profiles. The single patient who did not display the pattern had a very small region of ARIA-E and had been under treatment for a significantly longer period before the swelling became evident, which may have obscured regional differences. Without brain tissue analysis, the researchers cannot definitively conclude whether the amyloid is actually eliminated or simply concealed from the scanner.

Nonetheless, the consistency observed across four of the five patients is compelling. The team is now broadening its sample and working with the LEADS consortium to confirm the results in larger, more diverse populations. With nearly 7 million Americans currently diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and projections suggesting that number could double by 2060, any understanding of how these new treatments function within the brain is crucial.

For clinicians and families dealing with the uncertainties of anti-amyloid treatment, this discovery presents a slightly altered perspective on a concerning side effect. While brain swelling remains a serious issue requiring careful management, it may also indicate that, at least in those specific areas of the cortex, the drug is performing exactly as intended.

Study link: <a href="https://www.ajnr.org/content/